Image Courtesy Gabe Border

Threads of Land: A History of the Site the Erma Hayman House Resides On

September 22, 2022 - September 16, 2023

In partnership with Stephanie Inman

This mural by Boise-based artist Stephane Inman interprets, through seven key moments, the story of the land on which the Erma Hayman House resides, from the region's Indigenous People to Mrs. Hayman's time onsite all the way through the urban renewal period of the 1960s and 70s, which significantly altered the neighborhood’s historic footprint.

Shoshoni-Bannock woman at Fort Hall carrying wood on back, 1036-3e, Idaho State Archives

Indigenous People of the Boise Valley

For thousands of years, the Boise Valley has been the ancestral, cultural, and traditional home of the Shoshone, Bannock, and Northern Paiute people. Tribes followed seasonal migration patterns and moved between the foothills, the surrounding mountains, and the valley. Euro-American movement through and settlement of what would become Idaho Territory in the mid-1800s devastated Native Americans’ established ways of life. Emigration, Mining, city building, ranching, and farming exploited natural resources and disrupted Indigenous subsistence patterns, forcing them to the edges of their homelands. Violence and discrimination targeting Indigenous people further threatened their health, safety, and autonomy. Idaho’s territorial governor arranged treaties with the Shoshone that the federal government never upheld or ratified. Federal troops began relocating Native Americans by force from the Boise Valley to the Fort Hall Reservation in eastern Idaho in March 1869.

Homesteading, MS086-GP-046, Boise City Archives

Fur Traders, Mining, and Settlement

Euro-American fur traders first arrived in the greater Boise Valley in 1811, and exploration and fur trapping and trading continued intermittently over the next several decades. Representatives of the British-owned Hudson Bay Company established the original Fort Boise near the confluence of the Boise and Snake Rivers (modern Parma ) in 1834. By the mid-1840s, Fort Boise and the surrounding valley had become stopover points on the Oregon Trail, encouraging more permanent settlement. The discovery of gold in the Boise Basin in August 1862 drew prospectors, miners, and other laborers in greater numbers. On July 7, 1863, a small group of settlers gathered in a cabin and platted the first ten blocks of Boise City. William Thompson and John McClellan homesteaded land near the Boise River in the vicinity of the modern-day River Street neighborhood.

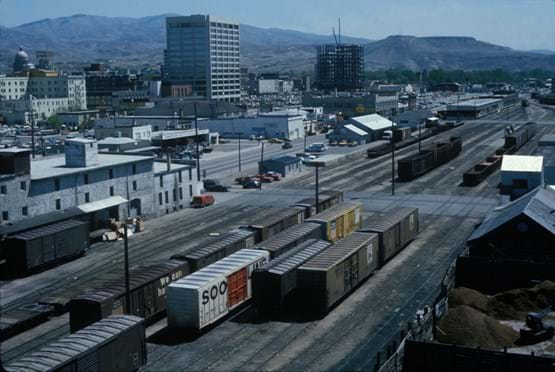

Railroad Yard Downtown, PO103-06, John Bertram

Population Growth and Infrastructure

As the city’s population grew, essential services followed. Boise was connected to telegraph service in 1875, the Independent School District of Boise City was established in 1881, and cultural institutions such as musical groups and theaters thrived. Residents also lobbied for a railroad connection to link the city to regional and national transportation routes. Rail lines were eventually laid along what is now Front Street, which created a physical barrier between downtown and housing additions platted closer to the Boise River. This contributed to the River Street neighborhood being known, pejoratively, as the “other side of the tracks.”

Quong Family, MS100-4827e, Boise City Archives

Development of the River Street Neighborhood

Housing discrimination and segregation pushed Black people and other minority groups, such as immigrants from the Basque Country, China, Russia, and Greece, to the city’s margins, and the area known as Boise’s River Street neighborhood developed as an ethnically diverse, working-class community. The enclave also supported a small commercial community that included businesses such as beauty shops and grocery stores. Pearl Grocery and Zurcher Bros. markets operated in the neighborhood for decades.

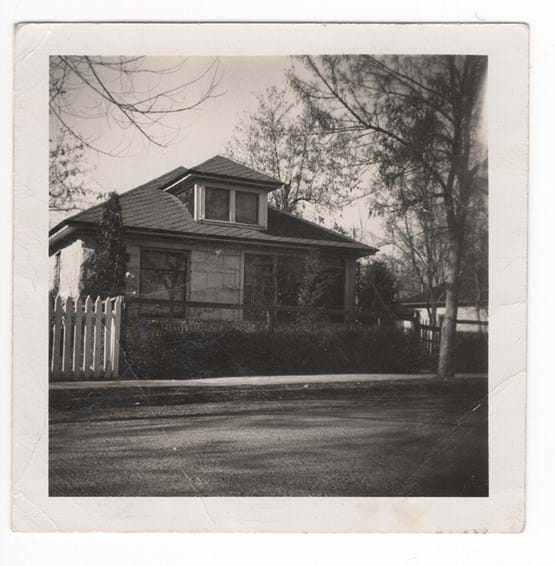

Erma Hayman House, MS078, Jeanne Madry–Young Collection, Boise City Archives

Housing Discrimination

During the early 1940s, the United States military constructed a large air base in Boise known as Gowen Field, which served primarily as a base for B-17 and B-24 bomber crews prior to their deployment in World War II. Development of the base brought new residents to Boise, and the city suffered from a housing shortage. Black service members who came to Boise with their families found homes in the River Street neighborhood when they experienced housing discrimination elsewhere in the city.

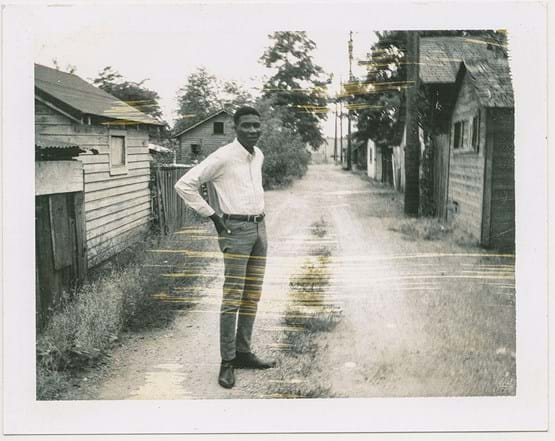

River Street Neighborhood, MS085-D01-03, Jerry Bridges Collection, Boise City Archives

The Green Book

In 1936, a travel book for the New York area provided crucial information to Black travelers about lodging, food establishments, and businesses that were non-discriminatory. Named the Green Book, the publication quickly gained popularity and expanded geographically to encompass locations nationwide, including Boise, Idaho. Boise locations listed in the publication included a downtown hotel, the Union Pacific Greyhound Depot café, and two tourist homes offering lodging in the River Street neighborhood—the Open Door Mission and the home of a Mrs. S. Love, both on River Street. Publication of the Green Book continued into the mid to late 1960s.

Demolition, MS097, Capital City Development Corporation Collection, Boise City Archives

Redevelopment and Urban Renewal

The River Street neighborhood changed significantly in the second half of the twentieth century, especially in the 1960s and 1970s when redevelopment projects—collectively known as “urban renewal”— began to alter the neighborhood’s historic footprint. Streets (including River Street) were realigned and widened, homes and structures targeted as “blighted” were demolished, and property was rezoned for commercial use. As a result, many of the River Street neighborhood’s early homes have been lost.